SHREWSBURY – To a casual observer, the old grave markers in Christ Church Cemetery in Shrewsbury all look about the same – old-style lettering, simply engravings, the dates and ages of the deceased. But on Thursday evening, Jan. 7, Monmouth University senior Taylor Cavanaugh presented the Shrewsbury Historical Society with a more nuanced view. “There were actually three distinct periods of iconography on the stones,” she told the audience of over 40 people. “Mortality imagery; cherubs; and finally neoclassical carvings each appear in defined clusters.”

A history and archaeology major, Cavanaugh just completed her senior thesis after spending months studying the numerous graves in the famed Episcopal churchyard at Broad Street and Sycamore Avenue in Shrewsbury. The young scholar spoke about her findings at the society’s headquarters and museum building just across the street from Christ Church. Both buildings are part of the historic “Four Corners.”

Last fall, Cavanaugh worked as an intern under the auspices of Christ Church historian Robert M. Kelly Jr. She studied, photographed, and analyzed about 50 individual headstones. She found a surprising consistency of styles within specific timeframes.

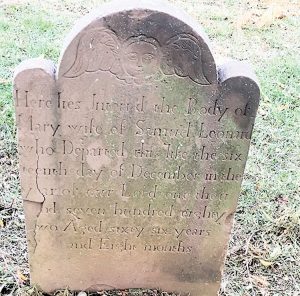

“The earliest and simplest grave markers in the churchyard date to the 17th century,” Cavanaugh observed. “Many of these stones have hourglass or death-head (skull) imagery. These primitive mortality images were used to remind the living of their eventual fate.” This style almost certainly originated in New England and was brought south to Monmouth County by settlers from the Rhode Island Colony. In fact, the stones themselves were probably quarried in Rhode Island, and then transported by ship to New Jersey.

The Shrewsbury community, largely agricultural in its early days, added specialty occupations like blacksmiths, woodworkers, and stone carvers in the mid to late 18th century. These small businesses generated wealth for their owners. Increased earnings and savings allowed people to buy more expensive day-to-day items like matched dishware and cutlery sets, and, of course, gravestones with more artistic carvings.

The second shift in grave stone imagery occurred after the Revolutionary War and was concurrent with the spread of new Protestant denominations. Cavanaugh documented a pattern of more elaborate grave marker carvings. Families who had made it to the top of society, like the Stelle’s in Shrewsbury, began to commission stone carvers to commemorate their deceased loved ones with fashion in mind. The memorials began to change from rococo (ornate, curving styles) to neoclassical ornamentation. Willow trees, urns, and monograms appeared. There was even some competitiveness as well-to-do families showed off their status by erecting taller headstones than their poorer contemporaries.