Story and photos by Rick Geffken

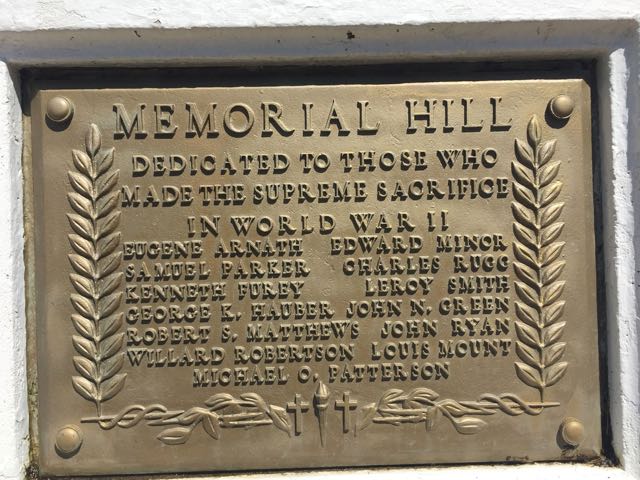

It’s easy to miss the small white stone nestled between the flagpoles at Veterans Memorial Park in Highlands. The hill rising near the Shrewsbury River is dominated by the tribute to thousands of 9/11 victims: two imposing bas-relief sculptures, and four engraved boulders. If you happen upon the small white stone you’ll see a bronze plaque inscribed with these few words: “Dedicated to those who made the Supreme Sacrifice in World War II.” The names of 13 Highlands men who died during that long ago conflict follow the inscription.

This unimposing tribute to a few deceased veterans did not escape the notice of Walter Guenther of the Highlands Historical Society. He found that the stone was originally in Huddy Park in the Water Witch section of town before it was moved to the park on the corner of Bay and Shrewsbury avenues. He strongly believes these patriots deserve to be remembered today, 71 years after the fighting stopped.

Guenther grew up in Highlands after his family moved from Nanuet in New York to Marine Place in the borough in 1943. “It seemed like all the older Highlands men were vets in those days. We played Army as kids in all our parks. I walked right by these names, didn’t know anything about them.”

After attending Cornell University and enjoying a career in corporate finance, Walt settled in Columbus, Ohio with his wife and children. They returned to Highlands every summer to spend time with Walter’s siblings and his mother. A few years ago, he joined the local Historical Society where his parents had been charter members. When he asked other members about the names on the World War II plaque, he was surprised that very little was known about the men. “I’ve always respected vets, though I’m not one myself,” he says. “They gave their lives for their country and we ought to know as much as we can about them.” Thus began his search to honor the service of the forgotten.

Walt estimated that at least three generations have passed since World War II, and it was unlikely any of the parents of the 13 were still alive. Who else might know about them? Remaining relatives might not often think about the men who shipped off to the Pacific or to Europe in the 1940’s. Sad memories fade, people move away, old photographs and letter molder away in attics or basements. Maybe some of these servicemen were just summer residents or even unmarried and therefore would have had no family connections at all in the Highlands.

Guenther visited the Highlands VFW and the American Legion Post to inquire about the names on the stone. “Nobody seemed to know. Same story when I went to Town Hall.” But he did discover that 265 men and five women from Highlands volunteered or were drafted for military service. “Thirteen deaths out of 270 seemed pretty high to me,” he recalls. Walter started digging in online resources like census records and newspapers. Obituaries for a few of the names yielded tiny biographical details. He found that all 13 were enlisted men, none were officers. One particularly heroic story emerged from Guenther’s investigations. That story revealed a Highlands family devastated by two tragedies.

Guenther visited the Highlands VFW and the American Legion Post to inquire about the names on the stone. “Nobody seemed to know. Same story when I went to Town Hall.” But he did discover that 265 men and five women from Highlands volunteered or were drafted for military service. “Thirteen deaths out of 270 seemed pretty high to me,” he recalls. Walter started digging in online resources like census records and newspapers. Obituaries for a few of the names yielded tiny biographical details. He found that all 13 were enlisted men, none were officers. One particularly heroic story emerged from Guenther’s investigations. That story revealed a Highlands family devastated by two tragedies.

Try as he might, Guenther could not find any military records for Ernest Arnath who died while serving in the Navy. Cross-checking the last name, Walt found that the man’s first name had been transcribed incorrectly. He was Eugene Arnath, and he was a decorated hero.

Arnath was a seaman on the USS Sculpin submarine patrolling the waters near Truk Island in the South Pacific in 1943. When a Japanese destroyer discovered it, the sub was subjected to a withering hour of depth charges. Forced to surface, the submariners were easy targets for the destroyer’s guns. The American crew scrambled to defend themselves. Eugene Arnath returned many rounds of fire from the sub’s deck gun until he was hit and killed. His heroism was rewarded with a Bronze Star. Many of his shipmates were killed, a lucky few captured.

We can only imagine the devastation on Arnath’s mother, Clara Bloodgood Rugg Arnath, when she received the awful news back in Highlands. Her grief was compounded when, less than a year after Eugene’s loss, another son, from a previous marriage, Charles Rugg, was also killed in combat.

Charles Rugg was a rifleman with the US Army’s 29th Infantry, one of the battalions which stormed Normandy Beach in France. Though he hasn’t yet discovered exactly where Charles died, Guenther believes Rugg made it off that beach during the famous invasion of 1944, but was cut down further inland just a few weeks later. Charles Rugg’s remains are with thousands of his comrades in arms in a U.S. cemetery in Normandy. We don’t know if Clara Arnath, a two-time Gold Star Mother – the designation used for women who lost sons during the war – was ever able to visit Charles’s gravesite.

At a June meeting of the Highlands Historical Society at the new Community Center, Walt Guenther revealed the personal stories of these men and the seven other deceased soldiers and sailors he has researched. Each deserves mention here:

Samuel Parker (Coast Guard), lost at sea in the North Atlantic in 1942

George “Red” Hauber (Navy), died during Battle of Santa Cruz, Solomon Islands, 1942

Michael “Oats” Patterson, killed in North Africa, 1943

Willard Robertson (Army), tank battalion trooper, died in Normandy in 1944

Lewis Mount (Army), killed during tank battle in Europe, 1944

Edward Minor (Navy), salvage diver lost off Norfolk, Virginia in 1945

Robert Matthew (Navy), aviation mechanic, MIA from aircraft carrier, Jan. 1946 (yes, records state his death as after the official armistice.)

Guenther is not discouraged that he has uncovered little about Leroy Smith, John M. Greene, Kenneth Furey and John Ryan Jr. The very evening of his talk, a historical society member mentioned she knew relatives of one of the deceased. Someone else gave him a newspaper article with promising leads to follow.

“Maybe someone who reads about this in The Two River Times will recall something, too. Or might recognize a last name associated with Highlands in those days,” Guenther says optimistically. Guenther is determined to pursue and publish the stories of these young, brave men.

Walt Guenther intends to write a full report on all 13 for the Highlands Historical Society. President Russell Card is confident it will be a valuable document for the society’s archives and all borough residents. “Walt found out so much in such a short time, I just know he’ll do a comprehensive job.” Walt plans to record all he finds on a CD, maybe even a book on the contributions of the men from this small town. “I’m going to give copies to the VFW and American Legion. A couple of generations from now, they won’t have to start from scratch for information on these brave guys.”