By Eileen Moon

In 1918, as World War I was raging in Europe, an invisible enemy had already begun an invasion much closer to home – an invasion that would prove far deadlier than the war itself.

Early that year, a new strain of influenza had begun making its presence known around the country, but its impact faded as spring gave way to summer and, here in the Two River area, life continued pretty much as before.

That October the Red Bank Register newspaper featured a Steinbach’s ad announcing the latest selections from Victor Records.

Songs like “When You Come Back,” “Laddie in Khaki” and “When the Boys Come Home” were on the playlist, along with some lively dance numbers like “When Aunt Dinah’s Daughter Hannah Bangs on the Piano.”

Downtown at the Empire Theatre, D.W. Griffiths’ “Hearts of the World” (“Created on the Battlefields of France,” the ad boasted) was set to play for three nights starting Oct. 14.

The Sigmund Eisner Company was looking for “girls over 16 years and women of all ages” to “Help Clothe the Army” by taking a job at its factory on Bridge Avenue.

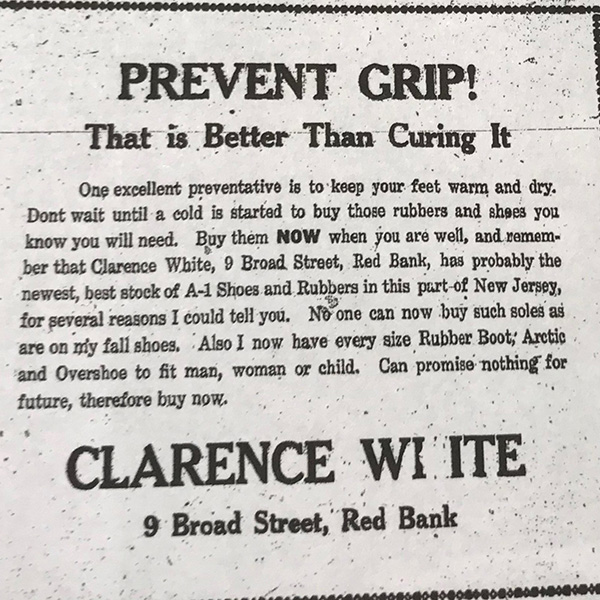

Laug’s Candy Shop offered peanut brittle (“Crisp and crackly, full of peanuts”) for 40 cents a pound while the Columbia Restaurant on Broad Street reminded readers of their “Businessmen’s lunch, 50 cents” and pastries “just like mother used to make.”

But life here was about to change in a drastic way.

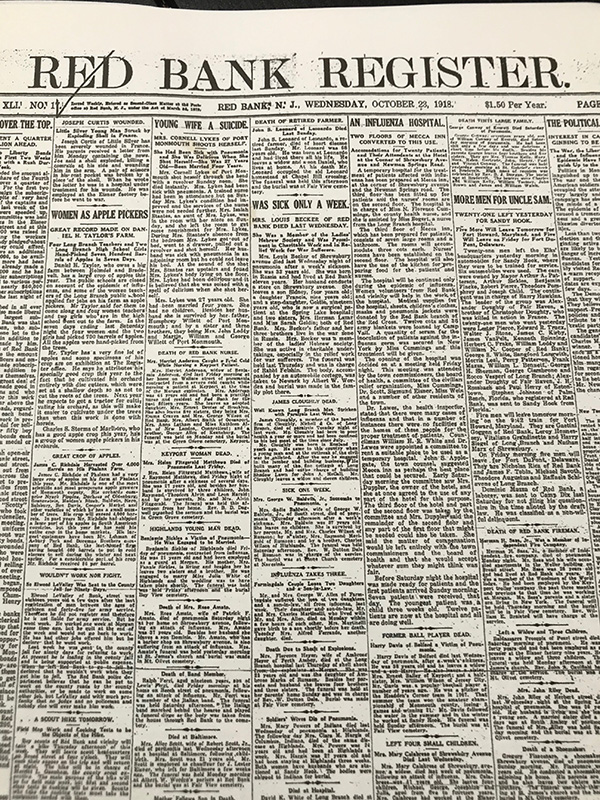

The headline on the front page of the paper Oct. 9, 1918 announced an “Epidemic of Influenza.”

“There has been a great spread of the epidemic of influenza during the past week,” the story noted. “The disease has spread over the entire eastern part of the country and every state board of health has issued directions to prevent its further spread and for the treatment of cases which occur.”

There was no cure.

Acting on orders from the state board of health, the Red Bank board ordered all public gatherings be avoided. A local Liberty Bond parade was canceled.

Movie theaters, churches, schools, dance halls, saloons, soda fountains, pool rooms and virtually any other place that people would normally gather were ordered to close. No public funerals were permitted and those suffering from the flu and pneumonia were ordered to stay in bed under isolation.

Red Bank physician Walter A. Rullman, a member of the board of health who also served as the medical examiner, urged the public to avoid crowds, sneeze and cough into their handkerchiefs, open their windows at night and gargle frequently.

Despite those precautions, the Two River area and many other cities and small towns across the nation were about to experience an epidemic of illness and death that nothing could have prepared them for.

In the end, New Jersey historian Brian Armstrong noted, more Americans would die of influenza in 1918 than in the combat trenches of World War I.

Armstrong’s interest in the influenza epidemic of 1918 began in childhood when he heard a family story about his grandfather, a native of Bar Harbor, Maine who was sent for his army training to Fort Devens, Massachusetts.

Arriving in early September, he soon became ill with what was then known as the Spanish Flu. Armstrong’s grandfather recalled two of his fellow soldiers flipping a coin to see which one would accompany his body back to Bar Harbor. But by the time he recovered, those two soldiers and the nurse who had cared for him had died from the disease.

Armstrong has included the family story about his grandfather in a book he is writing about the Spanish Flu as experienced in Bar Harbor. He is also the author of “The Franklin Park Tragedy,” (Arcadia, 2019), about an incident of murder and racial injustice that occurred in 1894 Franklin Park, New Jersey.

Although it was called the Spanish Flu, the 1918 virus is believed to have originated in Haskell City, Kansas when it was transmitted from an animal – probably a bird – to humans, Armstrong said.

It swiftly spread to soldiers stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas. As those troops deployed all over Europe, they carried the virus with them.

Because the nation was at war, censorship was heavy. Spain got the blame for the virus because Spain began to notice and report it while other nations restrained their coverage. “Spain was the only country that was not under censorship,” Armstrong said.

In the early months of 1918, a relatively mild form of influenza was in circulation, but the virus mutated during the summer of 1918. “It became a deadly version,” Armstrong said.

The United States had no national public health coordination at that time. There was no Centers for Disease Control and no World Health Organization “so it spread very rapidly,” Armstrong said.

That fall, the virus resurged in the Commonwealth Dock area of Boston, continuing a second wave that carried it to military bases and from there to cities and towns across the nation. “People would be out on furlough (on military leave) and would infect the towns,” Armstrong said.

Unlike the COVID-19 virus, the 1918 flu most commonly targeted people from ages 20 to 40.

Patients were prescribed – and sometimes overprescribed – aspirin. “People were dying of drug overdoses,” Armstrong said.

Then considered something of a miracle drug, aspirin’s primary manufacturer was Bayer, a German company, and America was at war with Germany, so patients here were given an aspirin equivalent made in the U.S., Armstrong said. Heroin was also used in an attempt to remedy breathing difficulties. Victims of the disease most often died of the pneumonia that followed a weakened immune system.

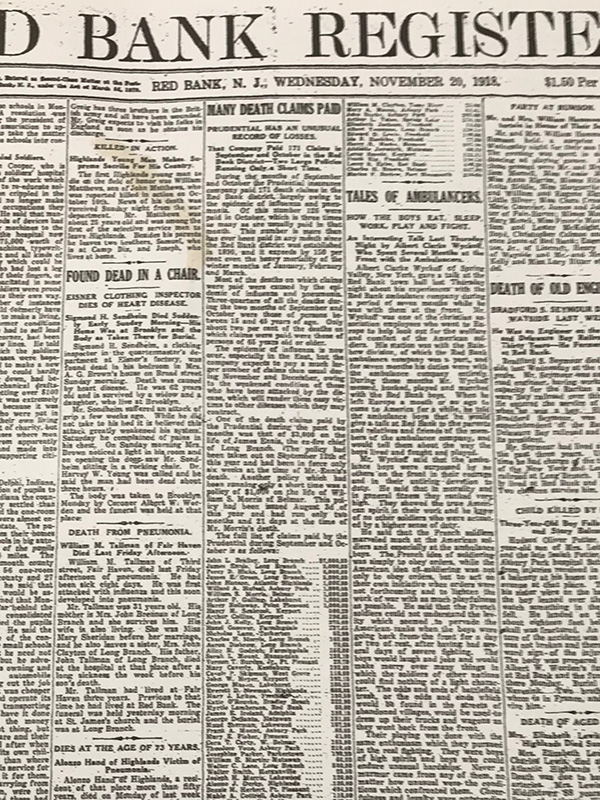

The peak of the influenza epidemic occurred in October and November 1918.

The headlines in the Red Bank Register tell the story. Reports of death from pneumonia – often within days or even hours of becoming ill – occupied its pages during the fall of 1918.

John Case, the manager of the Rumson Country Club. John Stewart, 24, who died after five days’ illness, while his brothers served in the Army overseas. A 12-year-old Red Bank girl, Helen Hartnedy, of pneumonia. Edna Brewer Lent, 22, who went to bed on a Monday after attending her sister’s funeral and died on Friday. A newlywed. A young mother of three. A former Long Branch fire chief.

Tragedies like those happening here were happening around the country. In New Jersey, Newark and Camden were hardest hit. Philadelphia, which had hosted a Liberty Bond parade against warnings, also experienced devastating losses. The peak of the illness occurred Oct. 22, 1918, when 7,000 new cases were reported across the country and 366 people died in one day.

Celebrities and politicians weren’t spared. President Woodrow Wilson contracted the virus, as did Walt Disney and then-well-known actress Lillian Gish. Well-known author Katharine Anne Porter transformed her experience with the disease into fiction in her 1939 book, “Pale Horse, Pale Rider.”

President Donald Trump’s grandfather, Frederick Trump, died of the disease while living in Queens, New York in 1918.

In the end, Armstrong said, approximately 29 million Americans – more than a quarter of the population – contracted the Spanish flu and approximately 675,000 died.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the 1918 flu was caused by an H1N1 virus believed to be of avian origin. COVID-19 is a new virus also believed to be of animal origin. Related to the SARS virus, COVID-19 was first identified in Wuhan, China.

It’s not the same illness but its potential for harm can’t be discounted, Armstrong said.

“I’ve been researching (the 1918 flu) for quite some time,” he said. “And I’m living this right now.”

The article originally appeared in the March 19-25, 2020 print edition of The Two River Times.