Photo by Philip Sean Curran

By Philip Sean Curran

A state lawmaker from Monmouth County has gotten behind a package of legislation aimed at creating more habitat for bees and other pollinators in New Jersey, where beekeepers point to various factors responsible for killing the bee population.

Assemblyman Eric Houghtaling (D-11), the chairman of the Assembly agriculture and natural resources committee, supports giving closed landfills a second life as pollinator habitats. A bill that he and others have sponsored would require the state Department of Environmental Protection to create a program encouraging “the owner or operator” of such landfills to turn them “into habitat that supports animal pollinators using native plants where possible,” the proposed legislation reads in part.

Another bill would require the state DEP to start a “leasing program” of state-owned lands for either private or public entities willing to manage them for pollinator habitat. According to the federal Department of Agriculture, honeybees pollinate more than 100 types of crops in North America, making them critical for the nation’s food supply.

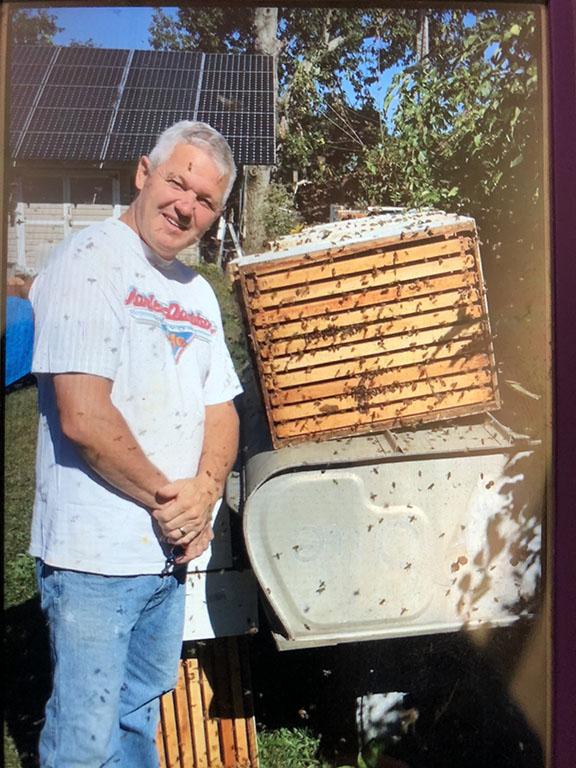

“We need to have pollinators for farming,” Houghtaling said after touring the Millstone farm of small commercial beekeepers Angelo and Anna Trapani Sept. 13. “So we have to create that environment and we’re losing environment all the time.”

Photo by Philip Sean Curran

Houghtaling’s visit to the Trapani farm is one of many he makes in his role as a lawmaker to farms around the state. He has said he sees it as his way to get information firsthand from the farming community in New Jersey.

“And you hear it all the time when you’re out talking to the different farmers about all the different needs that they have, and pollination is one of them,” Houghtaling said about why he wants to create a nourishing environment in the state for bees and other pollinators. “So we have a lot of state property that we have, open space that we have, landfills.”

Anna Trapani said she and her husband have about 300 colonies of bees, of roughly 60,000 bees or more per colony, that produce honey and work as pollinators on farms and orchards in Mercer, Ocean, Monmouth, Somerset and Middlesex counties. A bee makes 1/8th of a teaspoon of honey in its lifetime, she said.

Trapani, a fourth-generation farmer, said she has been keeping bees “all my life.” It’s part of a family tradition that was passed down from her grandfather. Yet she said being a beekeeper today is “tough,” as she lost about 74 bee colonies during a span from fall 2018 to this past spring.

“No one will pinpoint what’s causing the death” of the bees, she said. “It’s a combination of things.”

The problem of bee mortality is a national one. Opinions vary within the beekeeper community about what is behind the high rate of bee mortality, from pesticides sprayed on lawns to development stripping away natural land that bees otherwise might use for forage.

“The challenge is we’re destroying habitat,” said beekeeper Geff Vitale, of Kingwood, Hunterdon County. Dressed in a yellow shirt with the image of a bee on it, he came to the Sept. 20 meeting of the Central Jersey Beekeepers Association in Freehold.

Photo courtesy P. Ptak

Peter Ptak, of Ptak’s Apiary in Red Bank, keeps bees as a hobby; he is a pilot full-time. But his bees make anywhere from 600 to 1,000 pounds of honey a year.

“It’s a labor of love,” said his wife, Tanya Ptak, seated at a table inside the Monmouth County Agricultural building, where the meeting was taking place. Bee mortality has been an issue for years. The federal Environmental Protection Agency reported that beekeepers lost 30 to 90 percent of their hives during the winter of 2006-07. Since then, there has been continued loss of bee hives in high numbers nationally.

Ptak said that in one year, he lost 75 percent of his hives.

Trapani feels one big cause is mites, small bugs that feed off bees in their formative stages and cause deformities.

“So when that bee is born, …the mouth might be deformed, the wings might be deformed and they’ll just die,” Trapani said. “The hive will dwindle.”