By Melissa Ziobro

FORT MONMOUTH – The team behind The Fort Athletic Club in Oceanport has breathed new life into the old Fort Monmouth gym. Before the Department of Defense Base Realignment and Closure Commission shuttered Fort Monmouth in 2011, the building was known as the Abramowitz Field House.

What would become the Abramowitz Field House at Fort Monmouth was built after the previous post gym, located in a World War I era airplane hangar, was deemed unsafe and razed in 1950. While planning for a new facility evolved, Fort Monmouth’s many soldier-athletes hosted their opponents at places like local high schools and Asbury Park’s Convention Hall.

Over the years, the base had its own basketball teams, baseball teams and football teams, and hosted boxing and wrestling matches, and horseshoe tournaments. There were bowling leagues, swim meets and more. Sports were deemed critical for both conditioning and morale.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers architects drew the plans for the new athletic building, which included an indoor swimming pool measuring 75-feet-by-42-feet; a smooth, hardwood court measuring 90-feet-by-50- feet; and courtside seating with folding bleachers to accommodate 2,500 fans. The building’s floor plan allowed up to six different sports to take place at once.

The Gumina Construction Company of New Brunswick served as the general contractor for the building project. Park Steel and Iron Works of Bradley Beach provided much of the construction material. The new field house cost almost $1 million to build and equip. Profits from post exchange and motion pictures sales at U.S. military bases across the nation and abroad funded the construction. The building boasted the latest amenities, such as an electric scoreboard, tout- ed at the time as an innovative technology.

The first activity in the new field house came in early January 1952, a basketball double-header. The Fort men’s team, the Signaleers, played against the Cape May Coast Guard in the featured contest, while the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) team played the squad from the New Jersey College for Women (now Douglass Residential College of Rutgers University-New Brunswick). The Fort Monmouth men’s team won 64-48; the WACs lost 52-15.

Countless sporting events, often benefiting charity, would be held in the field house from that point forward, contributing to the physical conditioning, morale and welfare of the thousands of troops and their families stationed at what was then known as the “Home of the Signal Corps.”

As time went on and fewer uniformed military personnel and more government civilians worked at the fort, the field house, also referred to as the athletic center or gym, would also be used by those civilian employees and even by local public schools.

The Fort Monmouth Memorialization and Tradition Committee named the well-used field house after soldier, athlete, teacher and all-around Fort Monmouth legend Lt. Col. Reuben Abramowitz in a June 7, 1985 ceremony. Abramowitz’s story is right out of a Hollywood movie.

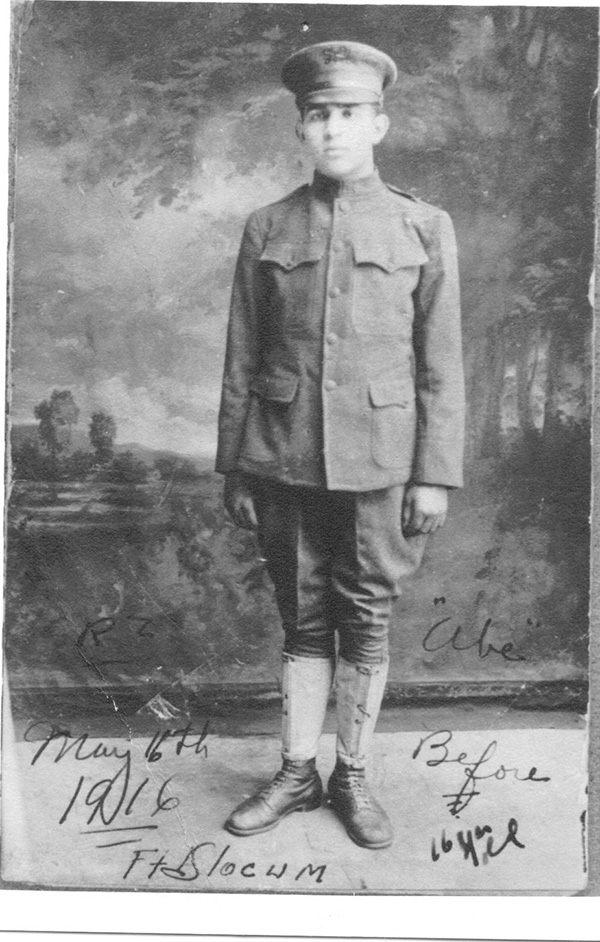

Five-year-old Reuben and his family came to America from Ukraine in 1906 and settled on the Lower East Side of New York. Rueben’s father died shortly after their arrival, leaving behind a family of five children and a widow who spoke no English. Reuben began delivering flowers and selling newspapers when he was just 6 to help support his family. His formal schooling ended when he was 9 years old. By May 1916, Reuben – just days shy of his 15th birthday – fibbed about his age to enlist in the military.

During World War I, he served overseas in France and then on occupation duty in Germany until August 1920. During this tour of duty in Europe, the young enlisted man was active on the Army rugby and boxing teams.

Abramowitz returned to the U.S. in late 1920, serving at Camp Alfred Vail, the precursor to Fort Monmouth, for a period prior to a three-year tour in Hawaii as a radio operator. While in Hawaii, he fulfilled his love of sports by playing on his unit’s basketball team. He then returned to Fort Monmouth and began an extended stay at the post.

During this period prior to World War II, Abramowitz maintained his keen interest in athletics. He directed the Fort Monmouth football and boxing teams and was for a period president of the Monmouth County Football Association. He even found time for romance, marrying Miss Olga Holtz of Long Branch in 1933.

But as global tensions heightened, Abramowitz’s key concern was hastening the training of radio operators. Under the system existing in 1930, it took approximately 100 hours to teach a man to type. Only after he finished his typing course was a soldier trained to coordinate that typing with code, which he would have learned separately. In peace time, the length of time taken to master and coordinate these two seemed inconsequential to many. But Abramowitz realized that, should the U.S. ever go to war again, well-trained radio operators would be in high demand. The Army would not be able to wait months for them to be trained. Abramowitz believed it possible to train radio operators in about half the time previously deemed necessary if a “reflex coordination” between the typewriter and the code could be achieved.

For example, under the old system, a man would learn that the tone sound “dah dit dah” signified the letter “K.” Accordingly, he would hand-write the letter “K.” Under Abramowitz’s new system, a student would be taught that the sound “dah-dit-dah” meant not only the letter “K,” but also the appropriate finger on the appropriate letter of the typewriter, and so on and so forth. Abramowitz’s method of teaching recruits both typing and code simultaneously meant that the 100 hours formerly needed to teach typing alone sufficed to teach both typing and code. His method spread throughout the Signal Corps and to many commercial radio schools as well, greatly increasing the speed with which critical radio operators were trained.

This is just one of many possible examples that show Abramowitz was a man who repeatedly assessed needs and innovated solutions.

In fact, Abramowitz received the Legion of Merit at the end of 1944 “in recognition of exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding service as chief of Code and Traffic Section, Radio Division, Signal Corps Enlisted Men’s School, Fort Monmouth, during the period March 1942-October 1944.” The citation credited Abramowitz with creating “methods and devices for instruction of such value that they have been introduced into schools of this type throughout the Army… His spirit, influence, and zeal above and beyond the normal call of duty have made him a leader in his field and inspiration to the men of the Signal Corps in all theaters of operations.”

In December 1944, Abramowitz – who had throughout his career enjoyed an astonishing rise through the ranks and was now a lieutenant colonel – was assigned as Officer in Charge, Signal Center, Headquarters, European Theater of Operations. On July 1, 1945 he became commandant of the European Command (EUCOM) Signal School, Ansbach, Germany. He was also the first installation commander of Ansbach. This was quite an achievement for Abramowitz, considering he fled Europe with his family and came to the United States as a child only decades earlier.

By June 1948, the Abramowitz family was ready to leave Ansbach. Maj. Gen. Jerry V. Matejka, EUCOM signal chief, told the men assembled there for Reuben’s farewell, “You are attending the best school in Europe. The credit for this excellence must be given to its commanding officer, Colonel Abramowitz, who built it with his own hands… He’s not only a brilliant and imaginative man, he is also a tough customer who is not afraid of anybody.”

In a letter of commendation presented to Abramowitz, Lt. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner, EUCOM deputy commander, noted the officer’s “foresight, exceptional planning and organizing ability in setting up and running the school at Ansbach.”

Abramowitz, Olga and their son Ben headed back to Fort Monmouth, where, according to Abramowitz himself, “all old signalmen are at home.”

Reuben Abramowitz retired when he returned stateside. He had devoted over three decades of his life to the service, rising from private to lieutenant colonel. He served honorably in war zones, revolutionized radio instruction, and trained thousands of soldiers. He was much beloved by his men. He had been active as a participant and an administrator in half a dozen sports. He and his wife settled in the Fort Monmouth area, where they stayed until his death March 13, 1967.

At the ceremony dedicating the Abramowitz Field House at Fort Monmouth in 1985, Brig. Gen. Harry Karegeannes read remarks that said in part, “We celebrate more than just the naming of a building today. We celebrate that which has made America great. We celebrate what some might call ‘the American dream.’ We honor a man who came to these shores… from central Europe. As a youth… he enlisted in the United States Army. Little more than a year later he was in Europe again – this time fighting for the ideal of liberty – the ideal which had brought him and his parents to this country not too many years before… over the years as athlete and educator, he was, of course, something more. He was, first and always, a soldier. He had a fierce and dedicated loyalty to the army… so, we honor today an athlete, an educator and a good soldier.”

One suspects Reuben Abramowitz would be pleased to see the old Fort Monmouth field house, once named in his honor, again full of life, thanks to the folks behind The Fort Athletic Club.

Melissa Ziobro is a specialist professor of public history at Monmouth University’s Department of History and Anthropology.

The article originally appeared in the February 9 – 15, 2023 print edition of The Two River Times.