By Melissa Ziobro, photos courtesy Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund

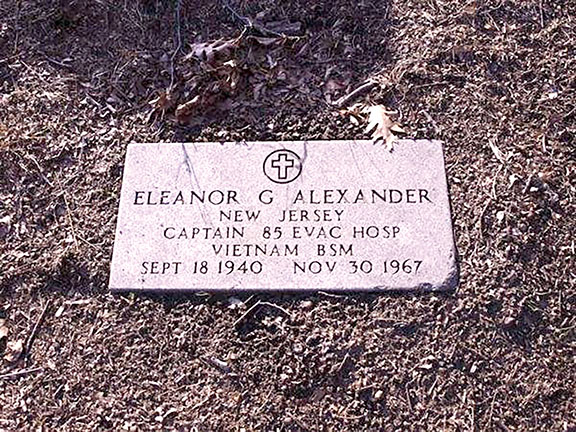

Nov. 30 is the 55th anniversary of the death of Capt. Eleanor Grace Alexander, a New Jersey woman who was killed in Vietnam – one of only eight military women to die in the conflict.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund reports that “more than 265,000 women served in the military during Vietnam – and approximately 10,000 military women served in-country during the conflict.”

The eight military women who died in Vietnam while serving their country are all memorialized on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C. In addition to Capt. Alexander, they are: 1st Lt. Sharon Ann Lane; 2nd Lt. Elizabeth Ann Jones; 2nd Lt. Carol Ann Elizabeth Drazba; Lt. Col. Annie Ruth Graham; 1st Lt. Hedwig Diane Orlowski; Capt. Mary Therese Klinker; and 2nd Lt. Pamela Dorothy Donovan.

This is the story of Eleanor Grace Alexander, the only woman of the 1,563 New Jerseyans who died while deployed during the Vietnam War.

Eleanor was born Sept. 18, 1940 in Queens, New York. Childhood friend Walter Haan recalled Eleanor as an intelligent and active girl who was moved up a grade in elementary school. Together, they tried to grow apple trees and played in the park. As they grew up, he recalled that Eleanor “was an attractive brunette and a lot of fun.”

Eleanor attended St. Michael’s High School in Manhattan, graduating in 1957. She went on to study nursing at D’Youville College School of Nursing in Buffalo, graduating in 1961 with her Bachelor of Science. Following graduation, she moved to River Vale, New Jersey, “to be closer to family.”

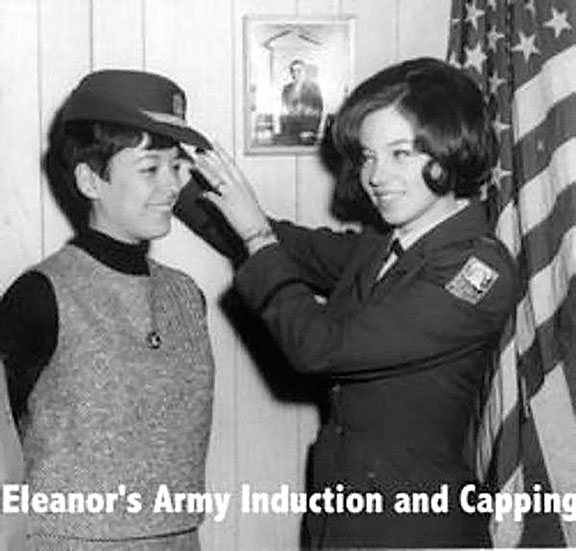

For the next six years, she worked as an operating room nurse at Madison Hospital in upstate New York before joining the Army Nurse Corps in May 1967. Though she was engaged to be married, she felt this was something she needed to do first.

Her friend Haan recalled fearing for her safety when she enlisted; urging her to serve her country in the Peace Corps instead. Undeterred, Eleanor finished her training at the Brooke Army Medical Center in Houston. She was assigned to the 44th Medical Brigade, 85th Evacuation Hospital, 55th Medical Group, and began her tour in Vietnam June 6, 1967.

The 44th Medical Brigade “was constituted in the Regular Army on Dec. 30, 1965. The brigade was activated on Jan. 1, 1966 at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, the home of the Army Medical Department. In April 1966, the Brigade moved to Vietnam where it participated in 12 of the 17 campaigns in which U.S. Forces were involved. During this tour the brigade was awarded two Meritorious Unit commendation streamers by the government of the Republic of Vietnam. In March of 1970 the personnel at the brigade headquarters were consolidated with those of the U.S. Army Vietnam Surgeons Office to form the Medical Command Vietnam and the brigade colors returned to the Continental United States in December 1970.”

While serving with this impressive unit, Capt. Alexander was killed on Nov. 30, 1967. She was returning from temporary assignment in Pleiku, treating soldiers wounded in the battle of Dak To. The plane she was on crashed, killing all 26 aboard. Eleanor was just 27 years old when she died, and had been in Vietnam less than a year. She wasn’t even supposed to be in Pleiku, but had voluntarily taken the place of another nurse. That woman wrote to Eleanor’s family on the anniversary of her death for years.

Several days passed before the Department of Defense made the crash public. The New York Times announced on Dec. 4, “A twin-engine United States Air Force transport plane carrying 26 Americans and secret documents crashed Thursday in the coastal lowlands south of Quinhon… There were no survivors, but the documents were recovered intact. The crash site was in an enemy held area about 275 miles northeast of Saigon… for this reason, the accident was not reported until today. The delay permitted search operations to be concluded without giving the Vietcong any information on them.”

By Dec. 6, the Pacific Stars and Stripes offered a bit more detail, reporting: “Twenty-six Americans died last Thursday when their twin-engine transport went down in heavy jungle three miles south of Qui Nhon… There were no survivors. The plane carried four crew members, two US civilians, 18 Army troops, and two Air Force men. Cause of the crash is unknown. The plane was enroute from Pleiku to Qui Nhon. The last contact with the plane occurred when the pilot radioed to Qui Nhon airfield he was bypassing them and flying to Nha Trang due to bad weather.” The article noted that the bodies were recovered intact, but did not identify the victims.

The Dec. 11 edition of Pacific Stars and Stripes reported Eleanor “Missing Not as a Result of Hostile Action.”

Under the headline “Three Jerseyans Killed in Vietnam,” the Dec. 13, 1967 issue of the Asbury Park Press newspaper read simply, “Capt. Eleanor G. Alexander, daughter of Mrs. Gladys F. Alexander, Westwood, was listed as dying not as a result of hostile action. She had formerly been listed as missing.”

In an interview with The New York Times, Eleanor’s sister-in-law Susanne Alexander remembered cruising around in Capt. Alexander’s car, “gorging on napoleons before Sunday family dinner.” She recalled, “When we were having our napoleon sneaks, she told me she was going to go over there and do this before she had any obligations… she insisted on going over there for six months. She had to do this.” Susanne remembered the dread that sank in when she and her husband, Eleanor’s brother Frank, first heard about the plane crash, sharing, “We heard about it on the radio – the day we moved into our house… there was this plane crash, and I just knew.”

On Dec. 18, 1967, Capt. Alexander was buried in St. Andrews cemetery in River Vale next to her father Frank Alexander Sr. and her sister Marguerite, who had died of tuberculosis at 15. Frank Jr. and Susan held on to the hope chest Eleanor had been assembling, in anticipation of a marriage that would never come. Eleanor’s devastated fiancé wrote to the couple at Christmas time for decades.

Online accounts from soldiers describing Eleanor make clear that she was admired by her peers. One soldier remembered, “When we lost Capt. Alexander, everyone was very sad. We had lost young men from our unit, and I have to say that we had hardened ourselves against such losses and expected them. Capt. Alexander, however, was different, and her loss was felt by everyone, and grief cast a cloud over the 85th… I think that after we lost her, we all realized that we had idealized and loved her a little, and that she had made our lives in Vietnam a bit more bearable.”

Friend Fred Roa told the Asbury Park Press that Eleanor “is a very beautiful, very cherished memory for me.” They corresponded while she was away. He recalled that in the last letter he received from her, Eleanor “warned she might not be writing him for a while because things were so busy, she was working 12-18 hours shifts.”

Eleanor’s loss haunted fellow nurse and friend Rhona Prescott, in whose stead Eleanor had gone to Pleiku. She left nursing after the war, and went back to school and trained to be a therapist. She found work counseling veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome. Coping with her own memories, she spent years penning a letter to Eleanor, which she finally finished in 1991. Now made available by the Library of Congress Veterans History Project, it reads in part:

July 7, 1991

Dear Eleanor,

This letter was begun in December, 1968, meant for your Mother, but never completed. She died about two years ago. I wrote your brother over Christmas, 1989, but it is you to whom I must speak.

We met in Qui Nhon, June 29,1967. You outranked me by a few months, you, “supernurse,” the backboneof the O.R. there. Our supervisor, the Major, seemed to have some problems, the main one being her absence during the “pushes.” So you and I informally worked it out that we would alternately function as supervisor. I thought you were top notch; you never got rattled, never made mistakes, even managed to look well groomed. I, on the other hand, struggled daily with the tattered lives before me, with my anger and with my frustration and with my frizzy hair. How did you keep it together? You know, the guys really leaned on you. You and I triaged, organized, drove the men and prayed. I screamed at people but you didn’t. I really admired your strength and envied it. You told me many times though, that you wished you had the chance to do what I did before Qui Nhon – work under tents, get the casualties right off the choppers; be in the middle of the heat. When they assigned me to the emergency surgical team, you wanted my spot. We were to be available 24 hours a day, while on that team. When they called but couldn’t find me, you grabbed my gear and jacket, and went in my place to Pleiku, nearthe intense fighting and lots of casualties. When I found out I was secretly glad for you. Six weeks later, after the mission was over, your plane went down while coming back to Qui Nhon. It was so windy that day. Ironically, I was in a plane on the same flight pattern behind you. You crashed into a mountain deep in V.C. territory. There were bullet holes in the fuselage. Days later, after the monsoon rain let up and the area was secured, your body was recovered. At least you weren’t taken prisoner. Did you die instantly? Were you in pain? What did you think?I couldn’t keep it together to go to the memorial service. My way of coping was to get tranquilizers. After I took all the pills I slept and slept. Why did I survive and you die? Eleanor, I cry when I go to the Wall. I cry about your death. I think about it a lot, twenty-three years later. Was it God’s Will or did I screw up your destiny and along with it mine? I don’t know if I should feel sorry, guilty or what. Did I deprive you of life? Or did I recklessly allow you to live the experience of doing the ultimate in nursing, as part of that team? I wish I knew; maybe I don’t wish to know. You are a hero back in New Jersey.

I think they even dedicated a little park to you…

As I marveled at your organization and inner peace, you envied my experience in that Clearing Company, doing surgery, I.V.’s, debridement, everything. You told me you wished you had the chance to do something like I did – really significant. I always thought that you did your job at the 85th better than I did at the 616th. Well, however it really was, Eleanor, you got your chance before you died. It was because of me… both of these things, you getting your chance and you dying, not really, I tell myself, but yet, really.

I am struggling, still trying to make an impact, imperfectly as ever. I must succeed in helping other survivors like me, and I must do it for you.

Your Friend,

Rhona

Another letter to Eleanor, left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in D.C. by researcher and writer Doreen Spelts and made accessible online by the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, reads in part:

Dear Eleanor,

… I’ve heard the stories from the veterans who knew you in Vietnam. And I have read your letters. So I felt it was time to write to you. I’m not sure if any of the names etched on these wings of stone may have been men whom you or the other seven women may have talked to or touched. But one thing is certain. Somewhere there are nurses who tried his and her best to save these lives. Eleanor, since I’ve begun to get acquainted with you and the other seven women, I’ve learned to keep you close to my breast. Then when I feel I know you well enough to share a little bit of you with the world, I write about you. Over a year ago when I wrote your families I said, “I want to write about your daughter or your sister.” Shortly after that I received a letter from one of your mothers. In her grief, still fresh after nearly 20 years, she asked me why I did not go to Vietnam. She asked me what was I doing with my life at the time of her daughter’s death? I answered that I had chose to marry and raise a child. Then I explained to her that now I was also doing what I chose to do: Write these stories.

Sharing the stories of those who served – and those who made the ultimate sacrifice – is indeed one small way we can honor their memories.

Capt. Eleanor Alexander was posthumously awarded a Bronze Star and Purple Heart. Her name can be found on Panel 31E Line 8 on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., and on the Nov. 30 panel at the NJ Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial in Holmdel. The grounds there also host a plaque honoring Eleanor in a Women Veterans Meditation Garden.

Melissa Ziobro is a specialist professor of public history at Monmouth University’s Department of History and Anthropology.

The article originally appeared in the November 24 – 30, 2022 print edition of The Two River Times.