By Eileen Moon

When former Two River Times film critic Joan Ellis enrolled in a memoir writing class at Project Write Now (PWN) in Red Bank a few years ago, she took a step that would ultimately lead to some life-altering, multigenerational friendships and a published book.

Ellis’ book, titled “Permission,” is dedicated to her children, Kevin, Corson and Laura, and her nine “millennial” grandchildren, with a special nod to her granddaughter Willa, “who, when she was very young,” Ellis writes, “asked me, ‘Gram, did you have a life before you knew me?’ ”

The book is her answer.

Ellis was a little apprehensive on the day she took her first memoir class at Project Write Now. Though she’d been writing and publishing movie reviews for decades, she wasn’t accustomed to writing anything longer than 500 words.

Her instructor at PWN, Allison Tevald, was a little apprehensive, too.

At 86, Ellis was many decades older than the other students and Tevald remembers wondering how she would fit in.

“Joan walked in wearing plain slacks, sensible shoes, a bright blue sweater and a huge smile,” Tevald wrote in her introduction to Ellis’s memoir. “This could go so many ways, I thought… I waited to see what would happen.”

If anyone assumed Ellis’s grandmotherly appearance was evidence of a quiet, uneventful life, they were soon disabused of that notion. Ellis quickly became a class favorite, captivating her fellow writers with the wit and intellect that had served her well through a lifetime of adventures.

Born in New York City in 1931, her first home was a cottage on her grandmother’s property on Navesink River Road. Ellis’s great-grandfather, Franklin Murphy, a Civil War veteran, served as governor of New Jersey from 1902 until 1905. His daughter Helen would become Ellis’s imperious grandmother who, having been denied her own opportunity to go to college by her father, paid Ellis’s tuition at Vassar.

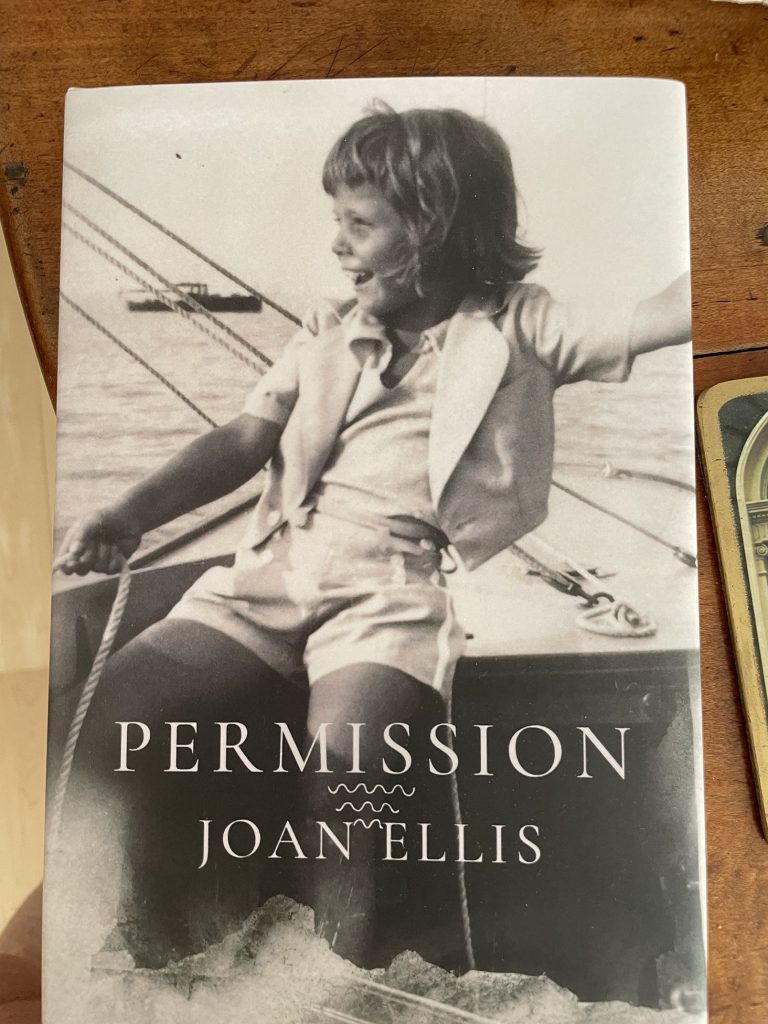

Ellis’s grandfather taught her to sail, letting her take the tiller as a very small child.

“I remember those days on the river, (being) alone in a short white boat and thinking how lucky I was,” Ellis said recently. “I didn’t want to be (a passenger). I wanted to make all those decisions.”

She entered Vassar College at 16, convincing the school to reverse their initial rejection and admit her despite her lackluster performance in high school. Ellis’s mother had lobbied for her to attend a junior college, have a coming out party, a debutante season, but she said no.

Soon, she was roaming the Vassar campus in a sweatshirt and cut-off blue jeans, a cigarette perennially dangling from the corner of her mouth.

She worked on the college paper, played the ukulele, sang folk music – desperate, Ellis said, to be seen as an intellectual. It was something of a no-rules school, Ellis wrote, making it near-impossible to get into trouble.

Unintentionally, however, she found a way: She was forced to drop out at 19 when she married her college sweetheart, Corson “Corky” Ellis.

“Back then, you couldn’t do both,” she said.

The newlyweds settled in New Haven while Corky completed his senior year at Yale. Their next stop was Washington, D.C., where both went to work for the CIA.

“I had always been fascinated with our American government and its role in international doings,” Ellis said recently, reminiscing about the old days as she sat in the living room of her apartment at the Atrium, a senior residence in Red Bank. “I worked for them for a long time. I loved it.” Following the family adventure in the spy business, Ellis moved with Corky to his various corporate assignments and the couple welcomed three children. Wherever her husband’s career took them, she would visit the local newspaper and ask if they were interested in publishing her film reviews. “I wrote in lots of different cities and places back then,” Ellis said. “There weren’t a lot of people writing reviews. I was very happy. I would take the kids to school and write all day.”

Eventually, they put down roots in the Two River area, building a home on Cooper Road on the Middletown side of the river.

Ellis was writing movie reviews for the Middletown Courier in 1990 when Two River Times founder Claudia Ansorge asked if she’d consider writing for her. Ellis would be The Two River Times film critic for the next 30 years.

By the time she retired in 2020, Ellis was a regular in PWN’s memoir classes, entertaining the class with anecdotes from her surprising life: getting homework help from future First Lady Jackie Bouvier Kennedy; refusing to get coffee for her boss at the CIA; her mothering years, a Wendy character in a Peter Pan-like paradise in the woods; entering Princeton University at 42, among the first classes of women admitted; her snowplowing business; her beekeeping.

“She’d surprise us in every class with a brand-new story,” Tevald said. “Her life just took on more and more dimensions.”

During one class exercise, 16-year-old Vivian Parkin DeRosa and then-86-year-old Joan were paired together with the instruction to stare into each other’s eyes for a full minute.

“I remember fighting the urge to laugh,” DeRosa wrote in her foreword to Ellis’s book. “But I knew, even then, that this wasn’t silly. Joan’s eyes were piercing in the real sense of the word. Like she could look right through me, past my Peter-Pan collar dress and hands clasped carefully in my lap and see me as I was… We met this way, eye to eye, and it was how we would always know each other, revealing ourselves.”

A few years later, with Ellis entering her 90s, her children reached out to Tevald for help in getting their mother’s book ready for publication. Tevald called DeRosa, asking if she would be interested in working with Ellis to compile the manuscript. Then taking a gap year from Smith College and full of uncertainty about the direction of her life, DeRosa welcomed the opportunity.

In the months that followed, she and Ellis met weekly for Zoom calls, reviewing the more than 7,000 Word documents Ellis had stored on her computer.

“I found the planned chapters Joan had written for her memoir, blog posts and movie reviews, letters, birthday cards, to-do lists. I was immediately overwhelmed by the mass because all of it seemed essential,” DeRosa wrote. “How best to tell the story of a life? It was a question that would come to define my own life.”

For DeRosa, the work on Ellis’s memoir had a powerful impact.

“My life intertwined with the stories Joan told me; her advice revealed us to each other, over and over again,” she wrote. “I came to understand that the records we create about our lives could be my life’s work.”

As the structure of the book took shape, Tevald and Ellis’s daughter Laura worked together to collate and caption the vast treasure of photographs that document Ellis’s many adventures, soliciting recollections for inclusion in the book from her family and friends about her impact on their lives.

When the project was complete, DeRosa returned to school, now sure of her direction.

She declared a concentration in archival studies, taking a job in special collections. After she completes her bachelor’s degree, she plans to earn a master’s degree in library science.

Ellis, meanwhile, is happy to share the adventure of her life with her family. “… memoirs used to be written only by famous people,” Joan wrote in her book.

“Now they can be a gift from all parents to their young. Every life is full of anecdotes that will be fun for the next in line.”

Now in her 90s, Ellis’s only concessions to advancing age are those she can’t avoid.

Names and dates slip from her memory; she has hung up her car keys but the world inside her head is rich and full of wonder. The view of the river she sees from the window as she writes is full of sails, some past, some present.

Once, she took the tiller and did not let go. Once, she drove a car when her feet could barely reach the pedals. Once, she fell in love with the magic of the movies and made that passion her career.

“I still love movies,” she says now. “I go to New York to see them and I certainly go to Red Bank and Middletown.” She still writes an occasional review or reminiscence.

“When I’m at home watching, I sit down, and I get out a pad and a pencil. I say to myself, ‘This has got to be the most fun occupation. Why doesn’t everybody do this?’ ”

Founded in 2014 by writer-educator Jennifer Chauhan, Project Write Now is a nonprofit organization dedicated to transforming individuals, organizations and communities through writing. PWN offers writing classes for teens and adults online and in person. To learn more about PWN, visit projectwritenow.org.