By Melissa Ziobro

HIGHLANDS – Visitors to Highlands usually notice the unique purple building at 78 Bay Ave. but most probably don’t know its storied history.

Occupied for over 50 years by local legend and true Renaissance man Carl “Tinker” West, the over 100-year-old building has a fascinating backstory that includes time spent as a theater, an automotive repair shop, a surfboard factory and a recording studio for local artists, including a young Bruce Springsteen.

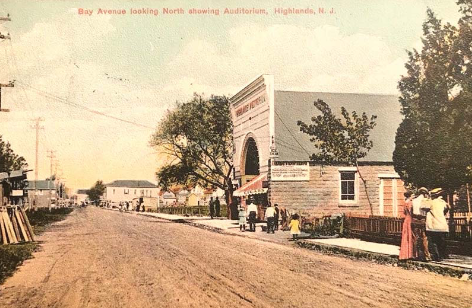

Early records are sparse, but the building was erected sometime in the early 1900s. By about 1906 the building was being used by Harry Sculthorp as the Highlands Auditorium Theatre, reportedly the first place in town dedicated to showing motion pictures.

Mae Schwind Bahrs, who grew up in Highlands in the early 20th century, recalled in a 2000 oral history interview with Flora Higgins that the town in those days “reminded me of a western town. Bay Avenue was a gravel road and there were hotels all along,” she recalled.

“You almost couldn’t walk down Bay Avenue (in the summer). If you wanted to pass somebody, you would have to step out on the road and walk around them. It was so crowded.”

The building operated as a theater into the 1920s. By 1923, a new theater opened at 88 Bay Ave. (now the Lusty Lobster). The old auditorium became known as the “Auditorium Garage.”

The building was used for automotive-related endeavors of various sorts until West came along in 1970.

West was born Aug. 7, 1935, in Culver City, California. He grew up with a stay-at-home mother and a father who worked long hours at a movie studio. West attended a junior college before transferring to UCLA and pursuing a degree in physics. He eventually worked with Briles Manufacturing, developing circuit breakers for B-52 aircraft.

He turned away from the defense manufacturing industry when he went to work for Wardy Surfboards, leaning into his lifelong love of surfing and learning to shape boards before moving on to Challenger Surfboards. Many of the surfboards he made shipped to the East Coast, to places like Maine, Massachusetts, Maryland and New Jersey. In fact, he realized more surfboards were selling on the East Coast than on the West Coast, so he got a 1950s Chevy, dubbed the “White Elephant” by local surfers, put all his tools and surfboards in it, and drove off to New Jersey in 1966, tempted by the low taxes and the state’s reputation as a manufacturing powerhouse. He started Challenger Eastern Surfboards and made a name for himself in the East Coast surfing community.

West allowed local bands to practice at his surfboard factories – ***if*** they played original music. He befriended, mentored and managed a number of local musicians, including Springsteen. Chapter 17 in Springsteen’s 2016 memoir “Born to Run” is titled “Tinker (Surfin’ Safari).” As Springsteen recalls, “He was called Tinker because there was nothing he couldn’t fix.”

“Ten years older and in twice as good shape as anyone in the band, he rode herd on the surfboard factory like the big kahuna he was.”

Springsteen and his early bands, like Child and Steel Mill, practiced regularly at West’s places, and Springsteen even lived with West for a spell. It was West who took the band out to California for the first time, teaching Springsteen to drive along the way.

As demand for surfboards waned, West sought a smaller building. Craig Statham writes in his book “Saint in the City, 1949- 1974” that around April 1970 West moved the surfboard factory to a building 78 Bay Ave., looking to return the building to its artistic roots. With help from a group of people, he gathered beams on the beach “torn from New York and New Jersey piers and boardwalks.” They used the beams to shore up the building and create a recording studio on the second floor.

Springsteen himself recalled the period in his memoir, “The Challenger Eastern surfboard factory in Wanamassa was now no more and we had a new clubhouse in a garage in Highlands… We’d built the interior of this dilapidated space ourselves, banging the nails, raising the walls, and insulating our recording studio. The whole thing was a classic off-the-grid, below-the-radar Carl West production.” West eventually purchased the property from Philip and Lillian Giaramita.

It was West who introduced Springsteen to his next manager, Mike Appel. Springsteen first auditioned for Appel in 1971 with West at his side. Appel told Springsteen to come back when he’d written more songs (something West himself had been constantly encouraging Springsteen to do). When Springsteen returned in 1972, Appel signed him and got him the audition with John Hammond of Columbia Records. This led to Clive Davis signing Springsteen. The Boss’s first two albums, “Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.” and “The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle,” both released in 1973, soon followed. The E Street band still practiced at 78 Bay Ave. on occasion during these years.

Did West, friend and mentor to so many local musicians, realize Springsteen had something special? He did indeed. In a 2016 oral history interview with the Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music, he said, “I thought he was great. You know why I thought he was great? Because of his ability to look at an audience and play a song, and if they didn’t like that, he’d go right away and play another one, a different one. He always had a stage presence, and he knew how to read an audience. He knew how to do all that stuff from the get-go.”

As Springsteen moved on, West remained a champion of the local music scene. He played a little guitar himself and managed and provided sound for other local bands. He let local musicians record demos in his surfboard factory/ music studio. And he organized large outdoor music festivals, all under the umbrella of Blah Productions. As he told a local newspaper in July 1972, Blah Productions got its name because “that’s generally what I think of the music business as it stands.”

In all the decades since Springsteen exploded to superstardom and the surfboard factory shut down, West has remained dedicated to creative pursuits. Though he no longer makes surfboards, he was inducted into the NJ Surfing Hall of Fame in 2015. He continues to maintain his workshop at 78 Bay Ave.

Springsteen thanked West when he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1999, lauding Carl ‘Tinker’ West as “another one of my early managers, whose support I couldn’t have done without.” Springsteen even remembered West’s building specifically when inducting the E Street Band into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2014, recalling “woodshedding out of a cottage on the main street of a lobster-fishing town – Highlands, New Jersey.”

The building’s purple paint job is a relatively new touch added by West, but historic features abound that attest to the building’s many different lives: the original sink, pieces of the original theater stage, the recording studio loft from the Springsteen days, and more.

Though it is in a redevelopment zone, Highlands has said they have no plans to condemn or otherwise forcibly redevelop the site.

Could “the purple building” be a candidate for a historic designation that might ensure its longevity? The general rule of thumb is that buildings should be 50 years old to be considered for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. The building can easily check that box.

Still, getting listed on the National Register can be a tedious process and it does not necessarily protect a building from demolition or redevelopment. Sites listed on the National Register do not have federal or state protection. Per the state of New Jersey, “The most effective protection of historic resources is designation and regulation at the municipal level.”

But whether or not it receives local historic status, 78 Bay Ave. – and its owner Tinker West – are true local treasures, not unlike the Boss himself.

Melissa Ziobro is a longtime educator with a passion for New Jersey history, and the newly appointed curator of the Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music at Monmouth University.

The article originally appeared in the October 26 – November 1, 2023 print edition of The Two River Times.