By Melissa Ziobro

FORT MONMOUTH – Horse racing enthusiasts will flock to the Monmouth Park Racetrack in Oceanport this summer, as they have since its opening in 1946. But that racetrack is not the first in eastern Monmouth County to delight residents and lure tourists to the area.

During the Gilded Age following the American Civil War, a world-class racetrack with its own luxury hotel flourished not far away, on land that would later become Fort Monmouth in Eatontown and Oceanport.

Improvements in steamship and railroad transportation during the second half of the 19th century allowed the Jersey Shore to become a convenient summer vacation retreat for many – harried New Yorkers in particular. Those of more modest means were day-trippers. Others could afford to stay at the numerous well-appointed hotels along the coast. The extravagantly wealthy rented or built their own “cottages,” usually positioned where they could take advantage of sea breezes.

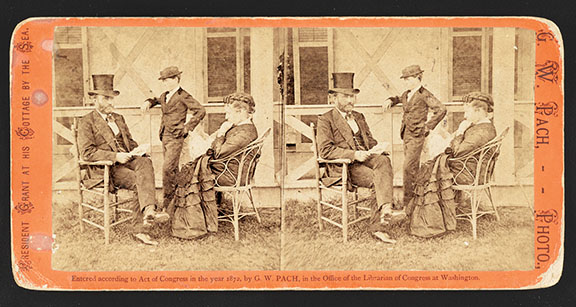

Long Branch in particular became the favored seaside resort of seven U.S. presidents: Ulysses Grant (1869-1877), Rutherford B. Hayes (1877-1881), James A. Garfield (1881), Chester A. Arthur (1881-1885), Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893), William McKinley (1897- 1901), and Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921). “The Branch” was even dubbed the nation’s “summer capital,” due to the frequency and duration of Grant’s visits.

To continue to boost tourism and compete with other resort towns like Saratoga, New York, some sought to bring horse racing to the area. According to The New York Times, the “myriads of fashionable visitors unanimously expressed their conviction that to make it the most attractive and delightful of water places, a racecourse and racing, properly and decorously managed, was the only desideratum.”

Among the entrepreneurs and politicians leading the charge were businessman – and avid gambler – John F. Chamberlin (sometimes spelled Chamberlain) and New Jersey Senate President Amos Robbins.

Chamberlin and his partners purchased a large parcel of land located just a few miles from the ever-popular Long Branch, straddling Eatontown and Oceanport. It was at the time a roughly two-and-a-half-hour trip from New York or a three-hour trip from Philadelphia. Chamberlin and his cohorts laid out an oval, 80-foot- wide, 1-mile racetrack that opened July 30, 1870. The 400-foot-long grandstand seated roughly 7,000. Racegoers came by horse, by carriage, by rail and by steamboats (or “floating palaces”) that made daily runs from New York City to Monmouth County.

Opening day was a slight disappointment. Famed financiers Jim Fisk and Jay Gould, as well as the infamous New York politician “Boss Tweed,” were among those present. While “Tammany politicians were as plentiful as they are on the eve of an election around the precincts of City Hall,” at least 2,000 of the grandstand seats went empty. President Ulysses S. Grant was noticeably absent.

That first season lasted just five days, with racing July 30 and Aug. 2-5. Local hotels and businessmen sponsored races. The New York Times declared the overall opening “highly credible… though not crowded.” The next season, in 1871, was declared “fair, though not flattering.”

Grant finally purchased a box and the masses soon followed suit. By 1872, a record crowd of 25,000 watched the “Monmouth Cup.” Racegoers filled hotels in surrounding towns to capacity. By 1873, The New York Times observed that the popular Monmouth Park denied Saratoga “her fair chance” at making a profit during racing season.

Even as the racetrack gained momentum, Chamberlin was accused of all manner of shady business dealings and mismanagement. The park went into default and changed ownership by 1878. After refurbishments, in 1882 the longest racing season to date took place. Purses and profits grew larger and larger; 1885 saw record crowds. The track became so popular that expansion beckoned.

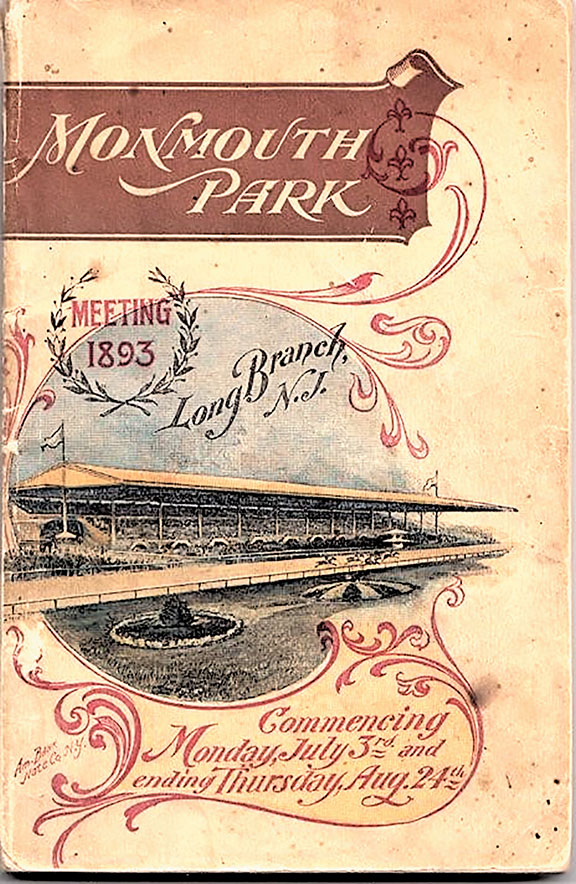

A bigger, more elaborate Monmouth Park was built just north of the original track. It opened July 4, 1890, and featured a 1 1⁄2-mile oval track and a massive steel grandstand for 10,000 spectators. The new park was said to be three times the size of the original and encompassed some 600 acres. It was touted as the largest racetrack in the world.

Everyone wanted to see and be seen at the new track, from politicians to businessmen to actors, actresses and socialites and what we today would call “influencers.”

One of the most amusing (if perhaps apocryphal) anecdotes from the era is that of actress and singer Lillian Russell riding to the track on a bicycle studded with diamonds. The bicycle was reportedly a gift from financier and philanthropist “Diamond Jim” Brady. Reporters and artists from the popular periodicals of the day – forerunners of paparazzi – followed the moneyed and famous about the racetrack and surrounding areas, desperate to capture exploits such as these.

The Monmouth Park experience proved so delightful that some people were reluctant to leave the grounds at all, so the Monmouth Park Hotel was built on Parkers Creek to accommodate them. The massive building had over 400 rooms. Amenities included an electric elevator, a smoking room and a billiards room. It was described as “the zenith of Victorian opulence with a surfeit of gold braid, silk tapestries, glass chandeliers, oriental rugs, and baroque staircases.”

The new racetrack was open for only one year when an anti-gambling faction in the state began pushing strongly to end legalized betting. By 1891 investors had moved many of the races to Jerome Park in New York due to all the uncertainty. At the time, The New York Times said, “This transfer will be regretted by very many people because of the hot and dusty trips to (other) tracks that will be necessary… The rapid and perfect service of the New Jersey Central and Pennsylvania Roads will be greatly missed, as will also the cool and pleasant nights at the Branch which have been so pleasurable to racegoers during the Monmouth Park season in past years.”

Local farmers, merchants and hotel owners also regretted the transfer of any races because the “closing of the track near Long Branch (could mean) a loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars to the various seashore interests.”

Despite the loss of some financial backing and races, the racetrack reopened for its 1892 and 1893 seasons. It is estimated some 30,000 people attended the 1892 opening, with The Times calling Monmouth Park “a perfect racetrack, and far and away the best in the country.”

But shortly thereafter, the park’s latest ownership, headed by Louisiana gambling magnate John A. Morris, entered into a very public feud with The New York Times after that newspaper ran a series of scathing exposés about the supposedly fixed races and unbeatable odds at Monmouth Park. Morris banned reporters from the park. The paper in return labeled Morris “the lottery king, who was spewed out of the state of Louisiana after he had prostituted that state to his purposes until the people would stand it no longer.”

By 1893, the same newspaper which had declared Monmouth a “perfect racetrack” one year earlier was warning readers that “the trail and slime of the lottery serpent about the racetrack is a little too much for decent people.”

The racetrack was forced to close for good after the 1893 season when the New Jersey legislature outlawed most forms of gambling in 1894. While some legislators tried to protect the track, they were overwhelmingly opposed and ultimately defeated by those listening to “ministers, priests, lawyers, and others.” Anti-gambling proponents could not be swayed in their belief that gambling meant “the ruin of young men by the thousands.” The Rev. S. Edward Young asserted that the “main magic that entices people to the track is the opportunity to gamble and get drunk, and more evil will be wrought at the track in eight weeks than all the pulpits can correct in fifty-two.”

An 1897 state ban on all gambling squashed any hopes of a Monmouth Park revival in the near future. The racetrack property was divided into parcels and auctioned. Deserted, the grandstand, track and hotel fell into ruin. A storm destroyed the grandstand in 1899 and the hotel burned to the ground in 1915.

Ownership of the various pieces of land changed several times before the U.S. Army Signal Corps leased much of it in 1917, following the American entry into World War I. Despite the fact that much of the site was overgrown and infested with poison ivy, it afforded the Army several advantages: proximity to the passenger terminal in Little Silver and to the major port of embarkation at Hoboken; good stone roads in the area, from when everyone wanted to get to the racetrack; and access to water. Remnants of the old Monmouth Park were scattered throughout the site, but the most prominent was perhaps a former ticket booth, which remained standing for many years. By the time New Jersey re-legalized racetrack gambling in 1939, the Army was firmly entrenched at the site.

The third Monmouth Park would have to move east, deeper into Oceanport, where it has flourished since 1946. If you visit this summer, think of those who placed their bets 153 years ago, during the original Monmouth Park’s first season – perhaps they will bring you luck!

Melissa Ziobro is the specialist professor of public history at Monmouth University’s Department of History and Anthropology. She served as a command historian for the Communications-Electronics Command at Fort Monmouth from 2004 until the base closure in 2011.

The article originally appeared in the June 8 – 14, 2023 print edition of The Two River Times.