By JF Grodeska

In only a handful of instances throughout the United States’ brief history have its shores been attacked by foreign forces. June 2, 1918, a date which would become known as Black Sunday, was one of those times.

World War I Rages In Europe

Czarist Russia had fallen to the Bolsheviks and the Kaiser desperately wanted to mount an offensive on the Western Front that would drive England and France out of the war before the United States could send a full complement of troops to aid the Allies.

However, the gamble failed, creating huge losses and casualties on both sides. Compounding this failure on the ground, the Kaiser’s U-boats were no longer stopping convoys of supplies making their way into England and France. What he did not realize was the Allies had broken the German submarine codes and were avoiding U-boat patrols in the Western Atlantic.

So, he decided to accept an idea born of frustration: They would convert several very large submarines that had been originally built as unarmed “merchant” submarines – in an attempt to run the highly effective British naval blockade – into U-cruisers (Untersee- boots-Kreuzer). Two of these submarines had made successful voyages to the United States in 1916 when the country was still officially neutral.

Armed with two 5.9-inch deck guns, two 20-inch torpedo tubes, 18 torpedoes, and mines, these were the largest – 1,500 tons and a crew of six officers and 50 men – and most heavily armed submarines in the world, possessing enough range to reach the U.S. East Coast and operate there for over a month.

A U-Boat Sets Sail Across The Atlantic

The U-151, originally named “U Oldenburg,” was one of these massive boats. On April 14, 1918, Korvettenkapitän (lieutenant commander in Allied terms) Heinrich von Nostitz gave the order to cast off and U-151 moved out of Kiel harbor on Germany’s Baltic coast. It would be a long patrol. The mission would be to disrupt merchant shipping off the coast of the United States.

The U-boat laid mines at the Delaware capes and cut the transatlantic communication cables linking New York with Nova Scotia. After several failed attempts to sink several ships, von Nostitz laid low and traveled up the coast, heading for better hunting grounds off the coast of New Jersey and New York Harbor.

On May 25, U-151 stopped three American schooners off Virginia, took their crews prisoner, and sank the three ships by gunfire.

And then came June 2, a day of shock for New Jersey and the country: Black Sunday, the first time a foreign enemy attacked the United States at home since the War of 1812.

Black Sunday Begins

At 7:50 a.m., the Isabel B. Wiley, a wooden three-masted schooner, was making her way from the port at Perth Amboy to Norfolk, Virginia. Unexpectedly, the crew heard a whistling sound, followed by an explosion off the bow. In the distance, Isabel B. Wiley’s captain, Thorn I. Thomassen, saw the silhouette of a submarine. The ship would be lost. He was given the time to allow his crew to man the motorboat and move away from the Isabel.

A short while later, the iron-hulled steamship Winneconne came into view, on the way to Providence, Rhode Island, with a cargo of 2,800 tons of coal, loaded at Norfolk. What happened next is best described in an interview in The Evening Star of Washington with Henry Walsh of San Francisco, Winneconne’s first officer:

“Third Mate Brewer called me up to the bridge about 10 o’clock Sunday morning. He told me that he had heard shots somewhere ahead. At that time, we were about sixty miles east of Cape May, and, looking ahead, I saw a three-masted schooner, with all sails set, lying nearly becalmed. There was enough wind to fill her sails and I though it strange that she was there, doing nothing.

Then I saw what looked like a destroyer come out from behind her. When we got about two miles away, I could see it was a submarine and that the men on deck were not dressed in white, as they would be at this time of the year on an American vessel.

Then I saw the German flag and the submarine sent a solid shot across our bows. They lowered a small boat, and a lieutenant came with some of the crew alongside telling us to get into the boats and row over to lay alongside the submarine. Just about the time we were leaving our boat, the men on what proved to be the Isabel Wiley were going over the side into their gasoline yawl. Of course, we obeyed, and all went to the side of the submarine, and the German crew first sank the Winneconne and then the Isobel Wiley with small bombs. The Winneconne went down in five minutes. They gave us officers time enough to save most of our things, and so I brought along my typewriter.”

Brewer, third officer on Winneconne, was from Booth Bay Harbor, Maine. He also spoke of the experience with U-151 after leaving his ship.

“When we bade good-bye to the submarine captain at 4 o’clock Sunday afternoon the weather was fine, and the sea smooth.

I must say that the German skipper treated us decently, for he sent a supply of water for the boat and some cans of black bread. He said that the bread was baked in April, and I did not eat it, because we had plenty of our own from our ship. The three boats of the Winneconne and the gasoline launch of the Wiley got together Sunday night, because I had a light in my boat. There were thirty in my boat, which was the biggest. With the men at the oars, we struck a course for Absecon Inlet, on the Jersey coast.”

Both Isabel B. Wiley and Winneconne rest in approximately 200 feet of water, 60 miles southeast of Barnegat.

But the U-151 and von Nostitz did not stop there. At 4 p.m. it bombed and sank the schooner Edward Cole in 185 feet of water. At. 5:20 p.m., it bombed and sank the freighter Texel in 230 feet of water.

The Jersey Shore Under Attack

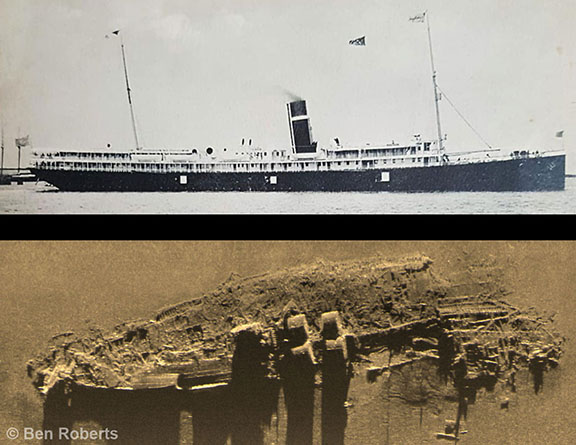

At 7 p.m., southeast of Sandy Hook, the cruise liner SS Carolina was on a voyage from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to New York with passengers and a cargo of sugar. The U-151 once again fired, this time across Carolina’s bow and she hove to. A German officer came aboard Carolina and gave the captain time to evacuate passengers and crew. During the evacuation 13 were killed when a boat capsized. Once all were away from the 380-foot liner, she was shelled and sank in 250 feet of water. In 1995, diver John Chatterton “arrested” the wreck and became the conservator/salvor of the Carolina. Later, he successfully salvaged the purser’s safe.

On her way out of the area, U-151 sank the schooner Jacob M. Haskell with bombs placed aboard after the crew was evacuated.

A Trail Of Devastation

U-151 sank six ships off the coast of New Jersey that Sunday in June 1918. In each case, the victims were contacted by the submarine and allowed to evacuate passengers and crew prior to being sunk.

U-151 returned to Kiel July 20, 1918, after a 94-day cruise in which she covered a distance of 12,561 miles. Von Nostitz reported that she sank 23 ships totaling 61,000 tons and laid mines responsible for the sinking of another four vessels.

At the end of the war, Germany surrendered U-151 to French forces in Cherbourg. The submarine was studied and the advancements disseminated to the Allies for use in their own navies. On June 7, 1921, U-151 was used as target practice and sank off the coast of Cherbourg.

Sadly, this would not be the last time German U-boats attacked the shores of New Jersey and New York Harbor. The World War II U-boat ace, Korvettenkapitän Reinhard Hardegen, during the night of Jan. 15, 1941, entered New York Harbor, nearly beaching the boat when he mistook shore lights for a light ship. The crew of U-123 were so elated when they came within sight of the city itself, all lights burning brightly, they asked Hardegen to let them have

their picture taken with the Statue of Liberty in the background. He surfaced the boat and the crew quickly assembled on deck for their photo opportunity. Hardegen took one picture himself and then posed for another with the crew. On the way out of the harbor, Hardegen sank the British tanker Coimbra.

The article originally appeared in the September 8 – 14, 2022 print edition of The Two River Times.