By JF Grodeska

The Atlantic Highlands of 1938 would be barely recognizable to someone living in today’s Bayshore town. Prohibition had repealed five years earlier. Gone were the bootleggers, smugglers and strong-arm artists that plagued the Bayshore in those dry days. Al Lillien, head of the Rum Radio Ring, had been murdered in his mansion on Serpentine Drive and most of the rest of the bootleggers were in prison, or on the run. The smart ones reinvented themselves – with the help of their rum-soaked wealth – into legitimate businessmen.

That summer of 1938 a man could walk into Tumen’s Clothing store and purchase polo shirts for 49 cents, slacks for $1.69 or dungarees for 79 cents. A woman could buy a linen blocked suit or dress for $1.49. You could buy tires for your car at Naylor’s on First Avenue, or coal from the Smith & Mausner Fuel Company at the foot of Mount Avenue. And, of course, you could buy the “very best meats in Atlantic Highlands and vicinity at Jagger’s Market: 92 First Avenue,” according to their advertisement in the Atlantic Highlands Journal.

In 1929, the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, despite a lawsuit filed by Mrs. Flora Morrison seeking to curtail construction, built an oil transfer station on the waterfront on the north side of Avenue D. On the South side of the street was The Atlantic Beach Amusement Park, stretching for some 17 acres along the east side of Bay Avenue to Avenue A.

Amusement in

Atlantic Highlands

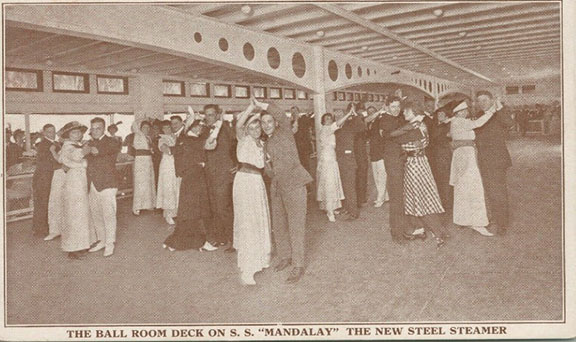

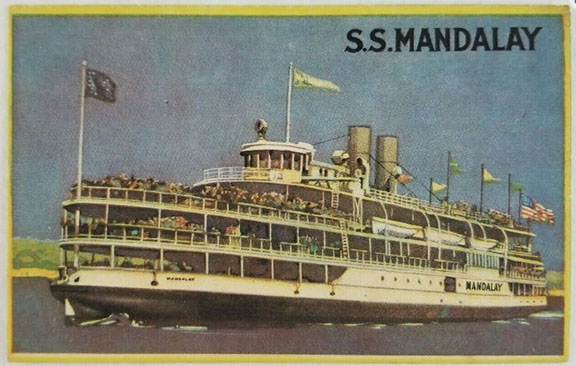

The Atlantic Beach Amusement Park began its first summer season in 1915 as Bayview Park, then as Joy Land Park, and then Atlantic Beach Amusement Park. Regardless of its nom de jour, the park was tethered to lower Manhattan’s Battery via the Boston, New York & Southern Steam Ship Company’s excursion ship, Mandalay. Mandalay became so famous to travelers, having carried over two million passengers to and from Atlantic Highlands over her 23-year career, that they referred to the amusement park as Mandalay Park.

The park’s main feature was a long roller coaster that was powered by ordinary automobile batteries. It also boasted an ornate carousel, imported from Germany, a 30-foot Ferris wheel, and “The Whip,” what we would refer to as bumper cars today. There was a midway with games of chance, Skee-Ball, a shooting gallery, a strength test where the guest would use a large hammer to ring the bell, a balloon and dart challenge, numerous food stands, a fortune teller, movie machines (called a Mutoscope) and a miniature golf course.

But no matter which amusement a guest preferred, getting to Atlantic Highlands meant a trip on the Mandalay.

The Day Turns Gray

It was 5 p.m. Saturday, May 28, 1938, the beginning of Memorial Day weekend. The afternoon was sunny and warm. As passengers walked up the gangway of Mandalay on their way back to the Battery, they were given a pamphlet with a picture of the ship on it and the lyrics and music to a song called “Dancing on the Mandalay” by Lee David. Passengers were encouraged to sing along with the orchestra – and they always did. Revelers lined the decks of the 292-foot excursion vessel and the Mandalay slipped away from the pier in Atlantic Highlands and began the trip home.

As the ship steamed across Sandy Hook Bay, the sky grew gray and a light fog developed. The Mandalay sounded her siren to warn approaching ships of her presence, since New York Harbor is one of the busiest harbors in the world.

By 6 p.m. that light fog had become thick and wet, driving most passengers inside. Mandalay continued to sound her siren at intervals, but now she was being answered by another vessel. The fog made it impossible to determine the direction of the other siren. Capt. Phillip Curran, master of the Mandalay for 12 years, could feel the tension of the bridge crew, as well as his own. While radar had been invented in 1904, there was little interest until 1942, when all U.S. and British commercial vessels had to be equipped with it to improve the navigation safety, as well as to enhance the detection of an enemy. Curran ordered Mandalay to slow her speed.

The Crash

Charles Eagan, a reporter with The New York Times, his wife, 9-year-old son and 7-year-old daughter were aboard the Mandalay that afternoon. He reported:

“I had gone out on the starboard deck near the spot where the Acadia later sliced into the side of the Mandalay. Looking through the fog, I saw the Acadia loom up on our Starboard bow. The ship, which had been moving very slowly, seemed to lose speed rapidly. Then I thought I heard someone shout from the Acadia, ‘Full speed astern, if you can!’ but the words may have come from elsewhere. Even so, I did not realize that a collision was inevitable until the Acadia was a few feet from the side of the Mandalay.

Then I braced myself. The bow of the Acadia struck the Mandalay with a loud crash and the sound of splintering woodwork. Under the impact, the Mandalay heeled sharp to port, with enough movement to have upset anyone not ready for the shock, and then snapped back to an even keel again. A few screams stopped almost immediately, and after that I witnessed no signs of fright among the passengers. Although I was told after that several people had jumped overboard. The prow of the Acadia extended into the side of the Mandalay some seven or eight feet. I noticed that the crew of the Mandalay were ripping down life belts from the racks above the decks. We all donned life preservers and I went back to the site of the collision.”

Assessing the situation, Capt. William B. Corning kept Acadia wedged tightly in the starboard side of Mandalay, keeping her afloat. The deckhands of Mandalay sprang into action, rigging a gangway from the second deck of the excursion boat to the bow of the 402-foot, 6,185-ton Acadia. Simultaneously, other crew members helped passengers of the stricken vessel into waiting lifeboats. Later, when questioned by reporters, Mandalay passengers would praise the crew and officers, including Curran, for calm and efficient acts of heroism.

One story talks of a steward passing a man on deck wearing his life vest upside down. Had the man entered the water, his head could have been forced below the surface by the vest. The steward stopped the man, stripped him of the vest and put it back on properly and cinched it so that it would not come off accidentally. All the while chatting pleasantly with a large smile as if nothing were wrong. The steward told the passenger there was no danger and went back to the business at hand.

As passengers were waiting for their turn to leave the sinking ship, Mandalay’s five-piece orchestra, led by Freddy Sleckman, kept on playing. The last song they played was “Dancing on the Mandalay,” the ship’s official song.

All the while Corning kept the Acadia’s bow wedged tightly in the hole in Mandalay’s starboard side, keeping the mortally wounded ship afloat.

The last person to leave Mandalay that night was Curran who, with tears in his eyes and overcome with emotion at the loss of the ship he had commanded for 12 years, stepped off the gangway onto the bow of the Acadia. He had not gone far when he turned and began running back to the gangway determined to go down with his precious Mandalay. Two Mandalay crewmen stopped him short of the gangway and persuaded him to sit down.

After the gangways were moved, the Acadia slowly backed off the damaged excursion vessel and Mandalay sank to the bottom stern first, 1 mile north of Swinburne Island, a 4-acre artificial island in Lower New York Bay, east of Staten Island. Sparks shot from her smokestacks. From the time of the collision to the recorded time of her sinking, 10 minutes had passed. Only 10 minutes to off load 314 passengers, and Mandalay’s crew – a monumental feat by any standards.

The Aftermath

Despite the collision and loss of the Mandalay, an inspection found that Acadia suffered little damage. She would continue on her way to Bermuda, though delayed by six hours. Passengers from Mandalay were transferred to Coast Guard and police launches and brought to the Battery. Reporters all indicated they were of good cheer and kept praising the actions of Mandalay’s captain and crew.

The next morning, and for subsequent days, headlines across the country – some from as far away as Hawaii – would carry the story of the sinking and the heroism of Mandalay’s crew.

But that night there was additional work to be done.

Mandalay sank in 40 feet of water. Her top deck and smokestacks were above the high tide mark. Her sinking in that area presented a problem for New York Harbor; she was a hazard to navigation. In the darkness, another vessel could easily smash into her.

The Coast Guard sent the cutter Icarus to set up a lighted buoy to warn ships off the wreck. Icarus remained on station to guide other vessels away from Mandalay.

In the aftermath of the sinking, like in all maritime and terrestrial disasters, the Federal Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation launched a federal inquest into the events of the sinking. Under the leadership if Capt. George Fried, the investigation found there were 11 injuries – one being the broken arm of one of Mandalay’s musicians – and that, contrary to rumors, no passengers were missing.

Crew members from both ships testified before investigators, all sea captains themselves. The testimonies lasted seven hours. Both crews and Capt. John Bolt a pilot on board Acadia at the time of the crash, testified in agreement with Capt. William Corning’s account of the accident. Corning said that Acadia was halted in the fog in the Lower Bay and that Mandalay “drifted across her path and crashed into her bow.”

Capt. Phillip Curran reported that the Mandalay had halted three times prior to the crash as other foghorns and sirens had been heard. She had, in fact, been halted in the fog, sirens blowing, when Acadia loomed out of the thick fog and slammed into her starboard side. Curran had given orders to put Mandalay’s port engines ahead and her starboard engines in reverse to attempt to bring the excursion vessel parallel to Acadia. He stated that there had not been enough time to complete that maneuver and Acadia sliced into Mandalay. During the testimony, crew members of each vessel declared that their vessel has been stopped at the time of the collision. A few claimed that the other vessel had been moving. Both captains conceded their vessels could have been drifting with the tide, but orders to come to a complete stop had been given and carried out. Acadia had deployed her anchor just prior to impact.

The board of inquiry stated that both captains, along with the pilot Bolt, should be credited with keeping Acadia and Mandalay wedged together, preventing Mandalay from sinking until all of the passengers and crew were safe.

On June 14, 1938, The Boston, New York and Southern Steam Ship Company, filed suit against The Eastern Steamship Line claiming negligence in the wrecking of the Mandalay. The lawsuit claimed that Acadia was traveling at a high rate of speed when she sliced into the 48-year-old Mandalay, sinking her. Further, Acadia was only 200 feet away when she loomed out of the fog. Though Curran attempted to evade impact, Acadia’s speed and close proximity made the maneuver impossible. Boston, New York and Southern Steam Ship Company asked for $750,000 for damages; Mandalay was insured for $495,000.

But there was still the dilemma of what to do with the wreck of the Mandalay in lower New York Bay.

Salvage and removal of Mandalay from the waters near Ambrose Channel began Aug. 27, 1938. C.F. Johnson Salvage Company of Lewis, Delaware won the bid. By the time they finished the job, furnishings and artifacts had all been sold and nothing of the Mandalay remained.

A Town Changes

The amusement park in Atlantic Highlands closed three years after the sinking, in 1941. The little train that took kids around the park was crated up and delivered to the boardwalk in Point Pleasant. The pier where the Mandalay docked was destroyed by fire. The east side of Bay Avenue, where Atlantic Beach Amusement Park stood, was developed into residential homes, and a new street, Harbor View Drive was created from Atlantic Beach. Tumen’s, Smith & Mausner Fuel Company and Jagger’s Market did not stand the test of time. However, Naylor’s Auto Parts Store did.

The Acadia went on to become a hospital and troop transport ship in World War II.

Atlantic Highlands legend says that Andy Richard, former bootlegger turned businessman, purchased a piece of the Mandalay and installed it in his tavern on First Avenue. The ornate mahogany bar that graced Andy’s Tavern on the corner of Center and First avenues was one of Mandalay’s bars. It resided there through each change of ownership. In fact, there was even a restaurant named The Mandalay at that location in the late 1960s. The bar was a piece of Atlantic Highlands history and, as such, priceless. The story goes that it was destroyed in the recent renovation of the property. One can only hope that last piece of history from a bygone age lives on in someone’s home or another establishment and the story of its destruction is only a story.

Thank you to the Atlantic Highlands Historical Society for providing information and some photos.

The article originally appeared in the August 11 – 17, 2022 print edition of The Two River Times.